Editor's Note – In the summer of 2012, Ansley Wegner, a historian with our Research Branch, wrote a series of blog posts highlighting various historical destinations around the state. This is the seventh post in that series. You can see all Wegner's posts on this page.

A couple of things crossed my desk recently that I wanted to share.

I got word about the upcoming annual homecoming in Pembroke this week for the Lumbee Tribe. There are a ton of educational and cultural activities, culminating on Saturday, July 7. Be sure to visit the Museum of the Native American Resource Center at Pembroke, too—they will open at 11 a.m. on Saturday, after the parade.

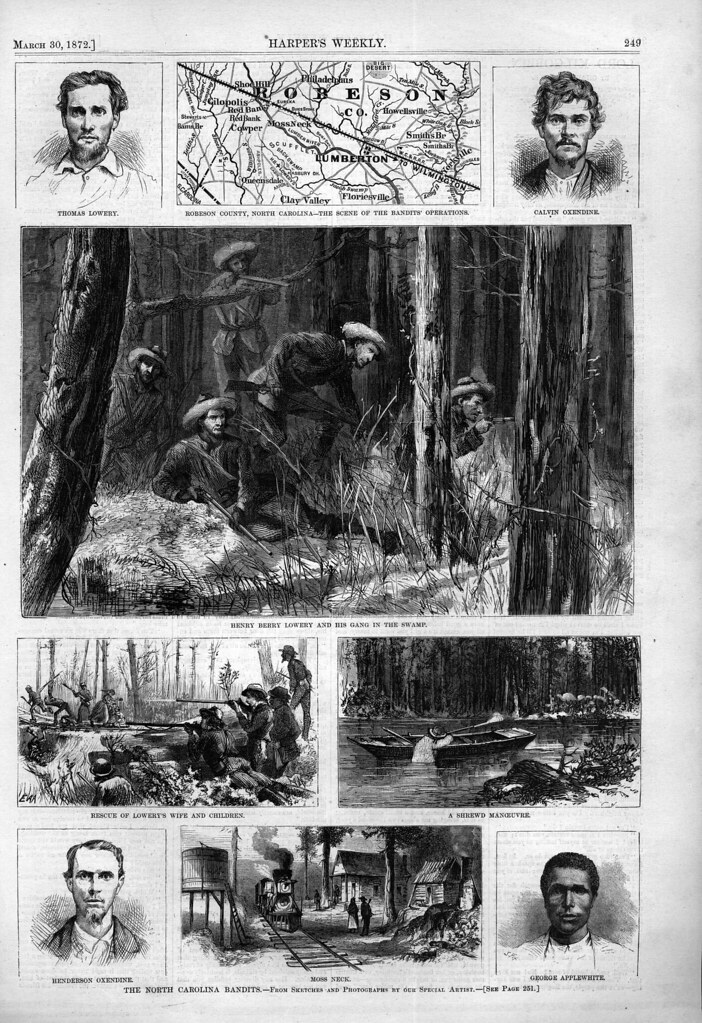

The other thing is that last week, while researching for my post on outdoor dramas, I found, sadly, that Strike at the Wind was no longer in production. The long-running play told the story of North Carolina’s own Robin Hood figure—Henry Berry Lowrie.

Viewed by some as a hero and by others as a criminal, Lowrie has been a legend ever since he disappeared in the swamps of Robeson County in 1872. There is a historical marker about him near Pembroke.

During the Civil War the Robeson County Indians (now known as Lumbee) were considered free people of color. And, as such, were often forced to perform hard labor for the Confederacy.Many Lumbees worked to build Fort Fisher or in salt mines. Lowrie and his brothers, like many young Lumbee men, took to the swamps of eastern North Carolina to escape forced labor.

The group began to raid the homes of white Robesonians, taking guns, clothing and supplies. Following a violent raid in February 1865, the Confederate Home Guard went to the home of Henry Berry’s father, Allen Lowrie, where they found items from the raid. Allen’s family was taken into custody and eventually, Allen and his son William were executed for the crime.

In March 1865 Henry Berry and his brothers, some cousins and a few other men embarked on a seven-year campaign of murder and larceny. Most of the men who were murdered by the band were in some way involved in the Lowrie executions.

During the height of the “Lowrie War” Henry Berry often appeared in public, and occasionally shared the spoils of his raids. His Robin Hood-like behavior made him popular among the poor.

Governor William W. Holden declared Henry Berry Lowrie an outlaw in 1868. A bounty of $10,000 was placed on him in 1871. Lowrie disappeared in February 1872 and the bounty was never collected.

Whether he was killed or whether he lived for a time after his disappearance we may never know.