Author: Matthew M. Peek, Military Collection Archivist

Every war has those who evade military service for various personal reasons, or desert from the military out of numerous reasons—including fear. There is a strong myth amongst academics in North Carolina that little resistance prior to the United States’ entrance in World War I in April 1917; and that after war was declared, North Carolinians came together to support the war effort general. However, that is not truly the case. Former mayor of Asheville, N.C., Theodore F. Davidson wrote an opinion piece that was published in early 1917 in the Greensboro Daily News newspaper issuing his opinion against the United States entering World War I. His article was widely circulated in North Carolina and the country, and Davidson received numerous replies to his article from North Carolinians all over the state who shared his view on neutrality. Most of the correspondence was from women or local officials in western and central North Carolina (more on this topic will be covered in a future blog post) [PC.100, Theodore F. Davidson Papers, Private Collections, State Archives of N.C.].

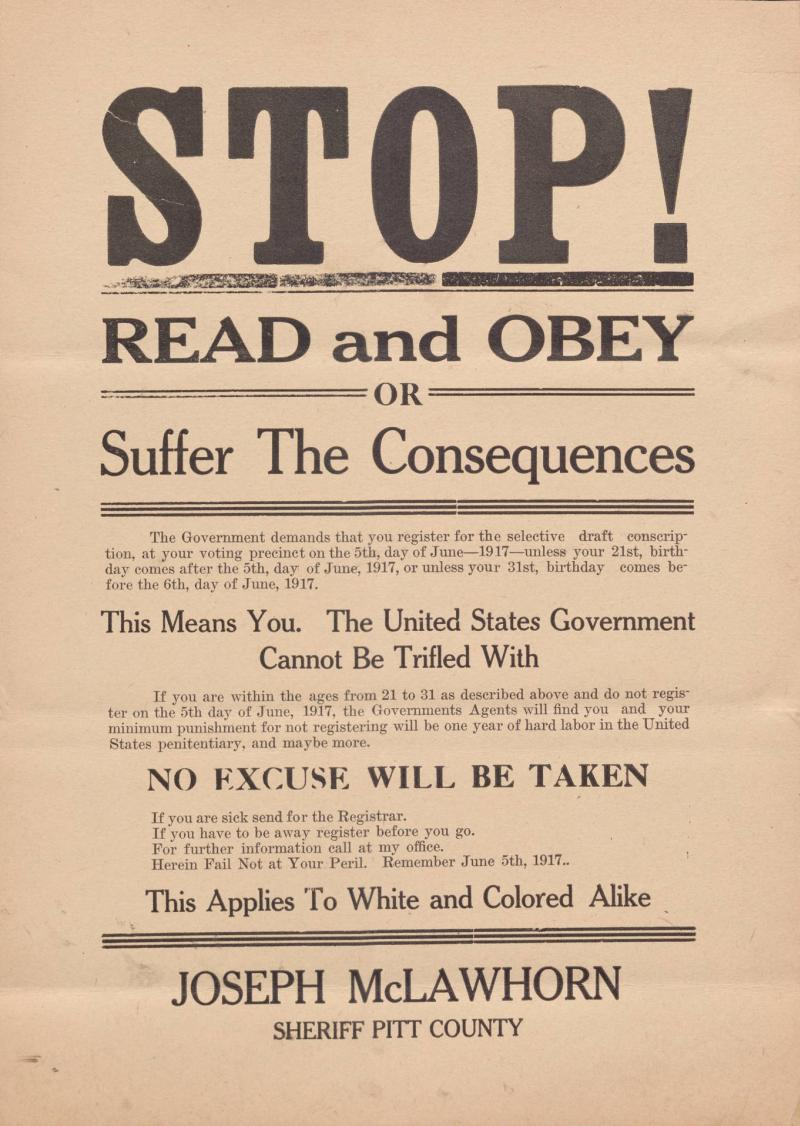

The first federal military draft and draft registration to be instituted since the U.S. Civil War—to begin on June 5, 1917—was met with confusion, fear, excitement, and a sense of duty to the country. Local officials had no idea had to enforce a county-wide draft with limited law enforcement officials, and what is today relatively slow means of transportation and communication. Without federal identity papers or identity establishment means such as Social Security numbers and cards, fingerprints, and DNA, local officials struggled to enforce federal statutes for a military draft that they had less than two months to prepare for. Many people were afraid what an international war would mean for the relatively young country of the United States, and how their families and lives would be affected by war. Women faced having to run homes, families, farms, businesses, and even local social institutions without the presence of a large number of local men—which during the period of the Progressive Era was a major social hindrance.

Young men were excited for an adventure before they knew the real horrors of a new type of mechanic warfare, designed for mass casualties and psychological terror. The majority of North Carolinians served because they had to, or because they felt a sense of duty to their country. North Carolinians were also afraid of the racial aspects of a federal draft, which forced black men to register for a war that the government was not going to let them really fight equally with white servicemen. Although they would not be used much for combat positions and instead suffered under menial military work, black North Carolinians were expected to report for the draft, complete paperwork that many could not read or fill out because of poor education, and threatened with punishments that could be unequally applied to black men. Poorer black North Carolina families that relied on the father or young men to support them would be spirited away to fight for a country that did not support them or allow for equal opportunities.

Desertion and draft evasion is a problem in every war of the twentieth century. However, World War I was the first war that the U.S. had to face with a draft. The federal, state, and local governments were experimenting with how to administer, conduct, and enforce a national draft, which left a lot of room for individuals to take advantage of the system. The draft system and its punishments varied from location to location. As the first modern war, WWI brought new fears and challenges to soldiers and their families. Men who had registered for the draft began deserting from military training camps between July 1917 and June 1918, as the hardships of the military, and often times the suffering of the draftee’s family without their loved ones’ assistance and income source, took their toll. Rich citizens attempted to buy their way or their sons’ way out of federal military service, or at the very least service on the front lines—a practice that the U.S. War Department worked hard to ensure not be allowed. Many individuals thought that they could escape registering for the draft or desert the military, and hide out away from their home areas where people would not know their history. Some men attempted to remain working civilian jobs that paid them well, for fear of losing the job upon returning from military service or to continue to make an amount of money that they knew the military could not compete with in pay.

Local county draft boards struggled to keep up with who was registered for the draft and who was not, at a time when mail and phone service were slow. Confirmation that some people registered in other locations, were living in different locations or states, had already registered but their records were lost or misplaced, or the wrong spelling of names—all of these things resulted in North Carolinians being accused of draft evasion. Deserters often left U.S. military troop trains on their way to military camps, or left the camps to return home, as they realized they did not like military life or did not want to go through the experience. The U.S. War Department worked with the various military branches, state governments and Councils of Defense, county draft boards, and local law enforcement officers to investigate the cases of draft evaders, deserters, and “slackers.” Slackers was a term used in WWI to refer to someone avoiding military service or being slow to respond to calls to report to the local draft boards.

The State Archives of North Carolina Military Collection’s WWI Papers holds a rare set of original records documenting deserters, slackers, and draft evaders, from around the state. The lists were created by local draft boards and regional military offices. They document the individuals’ names, home towns, ages, races, whether registered for the draft, action taken against the individuals, and comments about their particular case. A large number of the men featured on the lists are African Americans. Some men were actually underage, and the draft boards had the wrong information on the individuals. Some men had already registered in other counties—possibly because they were going to college nearby or living with other family members at a different address. Some men were in the hospital for medical issues and had not been able to register for the draft.

The lists indicate the wide range of reasons North Carolina black and white men had for not appearing to perform their duty as “loyal Americans,” as period propaganda exclaimed. Not everyone who did not register for the draft or who deserted the military did so for selfish reasons. Some men found out on the way to their training camps or while in camp that a family member was dying, or that the family’s house or farm was about to be lost for financial reasons. Some men simply were so poor and isolated in rural North Carolina regions that they had not heard of the draft.

The draft deserter and evaders lists cover the following geographic military districts of the state: Washington County; Wilmington Division; Wilson Division; eastern North Carolina military district (covering most of the eastern part of the state); Wake County; Elizabeth City; Buncombe County; Raleigh; and New Bern. Although the areas covered by the lists are indicated in the regional location names, they often contain people from areas other than that particular location, such as Durham County men showing up on the Wake County list, because it was the closest regional district for reporting the desertion or draft evasion. We really do not understand how the lists were created, as there is no documentation to go with them about the processing of registering the names and conducting the investigations. The lists are both handwritten and typed, and often indicate the results of the investigations. Not all of the men featured on the lists served in the military in WWI, which makes them an important record for WWI-era genealogy.

All of the draft evaders and deserters lists have been digitized, and are available to view in the WWI digital collection on the North Carolina Digital Collections (NCDC), a joint effort of the State Archives of North Carolina and the State Library of North Carolina.

You can also use the original draft evaders and deserters lists from the North Carolina Draft Records (WWI 3)—and other deserter records found in a number of other collections—in the WWI Papers of the Military Collection at the State Archives of North Carolina in Raleigh, N.C.

The North Carolina Genealogical Society has been partnering with the State Archives of North Carolina to transcribe the handwritten draft evaders and deserters lists, and will feature them in their NCGS Journal or through their members-only website portal.

This blog post is part of the State Archives of North Carolina’s World War I Social Media Project, an effort to bring original WWI archival materials to the public through the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources’ (NCDNCR) various social media platforms, in order to increase access to the items during the WWI centennial celebration by the state of North Carolina.

Between February 2017 and June 2019, the State Archives of North Carolina will be posting blog articles, Facebook posts, and Twitter posts, featuring WWI archival materials which are posted on the exact 100th anniversary of their creation during the war. Blog posts will feature interpretations of the content of WWI documents, photographs, diary entries, posters, and other records, including scans of the original archival materials, held by the State Archives of North Carolina, and will be featured in NCDNCR’s WWI centennial blog.