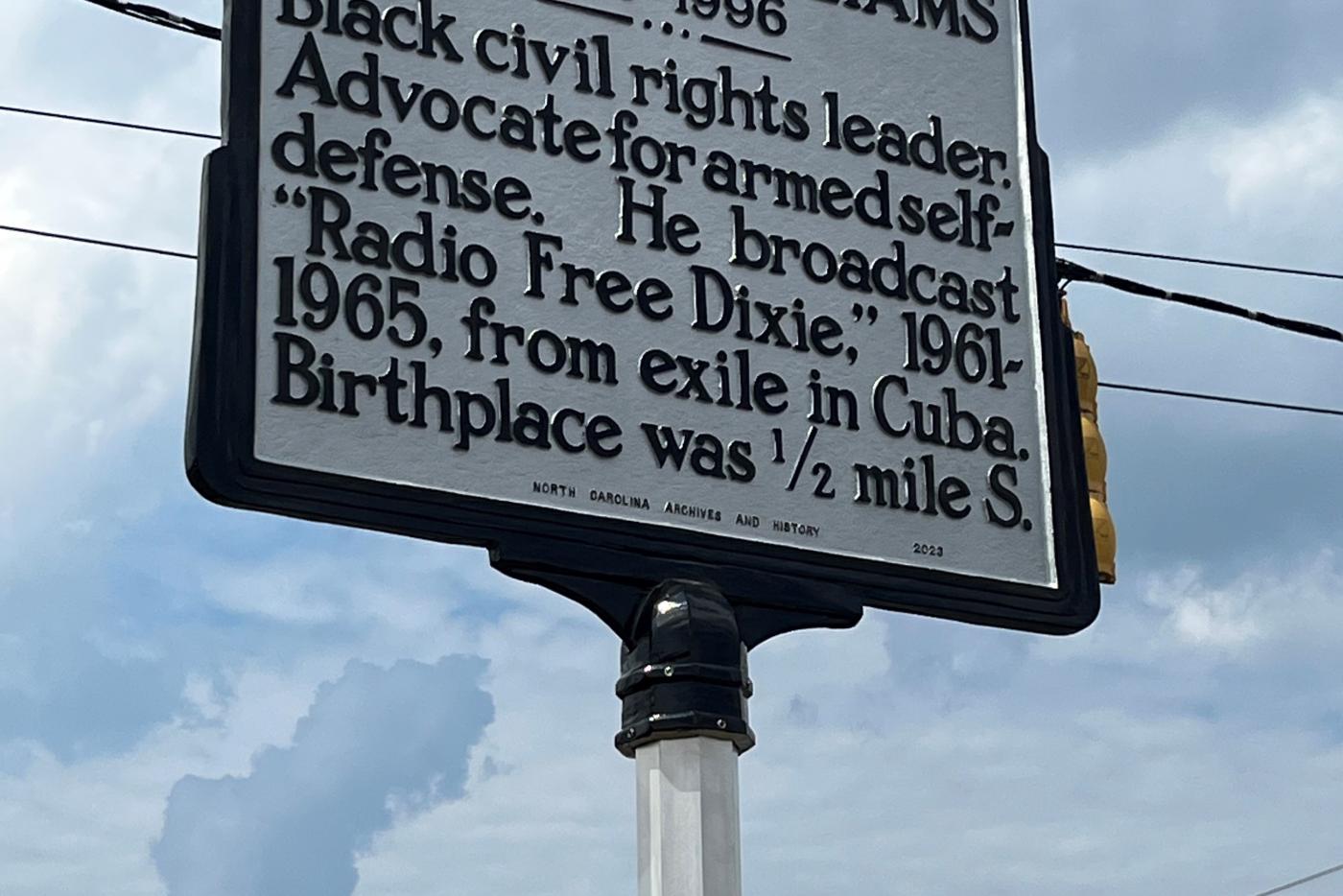

Location: SW corner of intersection of Hwy 74 (Roosevelt Blvd.) and Boyte St, Monroe

County: Union

Original Date Cast: 2023

Robert Franklin Williams was a major figure in the struggle for African American civil rights in the United States. He was born in Monroe, N.C., in 1925. As a young man he left Monroe and moved to Detroit, where he worked in an auto assembly plant and became active in the labor movement. After serving in the U.S. Army and, later, in the U.S. Marine Corps, Williams returned to his hometown and was elected president of the local chapter of the NAACP. Alarmed by the threats that Black civil rights advocates faced from white supremacists, Williams believed that African Americans should be able to defend themselves from violent attacks by violence if necessary. He applied for and received a charter for a National Rifle Association chapter. Calling it the Black Armed Guard, Williams recruited former African American military veterans like himself for much of its membership. In 1957 the Guard protected the house of Dr. Albert E. Perry, vice president of the Monroe chapter of the NAACP, from an attack by armed members of the Ku Klux Klan; Williams and the Guard drove off the Klansman after a brief shoot-out.

Williams’ ideas on armed self-defense were explored in his 1962 book Negroes With Guns, which proved highly influential on the views of Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party in 1966. At the same time, Williams utilized a variety of non-violent methods to achieve various integration goals. In 1959 he established The Crusader, a weekly newsletter which he edited, and which promoted the civil rights movement.

In 1958, Williams took an active role in publicizing the Monroe “Kissing Case.” Two African American boys who were only seven and nine years old had been kissed on the cheeks by a young white girl while playing a game. The boys were subsequently arrested, tried, and convicted on charges of molesting the girl, and were sentenced to juvenile reform school. The Committee to Combat Racial Injustice was organized to defend the children, with Williams chosen as chairman. The committee successfully pressured Governor Luther Hodges to pardon the boys in the following year.

When members of the non-violent Freedom Riders movement arrived in Monroe in 1961, they received Williams’ support. Tensions rose over the next few weeks as local white supremacists attacked members of the Riders. When a white couple from a neighboring town accidentally drove into a Black neighborhood, they were surrounded by local residents, who were convinced that their car was the same vehicle seen carrying a banner with a violently racist message on the day before. Williams brought them into his own house for protection, where they remained for about two hours before departing safely. With violence escalating in Monroe and having been threatened by the chief of police with lynching, Williams and his family fled Monroe in what was thought would be a temporary departure. He soon faced trumped-up charges from the FBI that he was in flight to avoid arrest for having kidnapped the wayward white couple. To avoid prosecution, he fled the country. He initially lived in exile in Cuba, where he and his wife Mabel broadcast “Radio Free Dixie” with Cuban government support to the United States. Although receivable around the country, Williams’ intended audience was African Americans living in the Southern states. The show contained a mixture of music, news, and commentary, with Williams’ rhetoric growing increasingly harsh and militant as his frustration with the slow process of change, increasing racial violence, and America’s domestic and foreign policies grew.

Williams and his family left Cuba in 1965 and relocated to China. In 1969, however, he returned to the United States. Living in Michigan, he fought to clear his name. Finally extradited to stand trial in North Carolina, the charges against him were dropped. He continued to live with his family in Michigan, where he died of Hodgkin’s Disease in 1996. He was buried in Monroe, where he was eulogized at his funeral by Rosa Parks.

References:

Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice (2006).

Marcellus C. Barksdale, “Robert F. Williams and the Indigenous Civil Rights Movement in Monroe, North Carolina, 1961,” Journal of Negro History 69:2 (Spring 1984), 73-89.

“The Black Scholar Interviews: Robert F. Williams,” The Black Scholar, 1:7 (May 1970), 2-14.

Robert Cohen, Black Crusader: A Biography of Robert Franklin Williams (1972).

Robert Carl Cohen Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

Timothy B. Tyson, Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power (1999).

Robert F. Williams, Negroes with Guns (1962).