Author: Jessica A. Bandel

In May 1918, the Department of Labor announced its intentions to ease the labor shortages hampering government projects by recruiting Puerto Rican laborers. The federal government planned to compensate the estimated 75,000 volunteers with affordable meals, free housing, a wage of thirty-five cents per hour, and overtime pay. Transportation from the island to the mainland United States was provided through the War Department, which used transport vessels to ferry laborers to the coast after dropping supplies at San Juan.

For many Puerto Rican citizens, the opportunity could not have come a moment too soon. The island’s agriculture-based economy was in the midst of a transformation, thanks in large part to the outcome of the Spanish-American War. The war’s subsequent peace treaty called for Spain to cede control of Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico to the United States. This opened the door for American corporate capitalists, who established several large-scale sugar plantations on the island, forcing many Puerto Ricans off their land and into wage-paying jobs.

For many Puerto Rican citizens, the opportunity could not have come a moment too soon. The island’s agriculture-based economy was in the midst of a transformation, thanks in large part to the outcome of the Spanish-American War. The war’s subsequent peace treaty called for Spain to cede control of Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico to the United States. This opened the door for American corporate capitalists, who established several large-scale sugar plantations on the island, forcing many Puerto Ricans off their land and into wage-paying jobs.

When the Department of Labor came calling, those looking for a chance at stable income volunteered. By the end of September 1918, 1,735 of the laborers had landed in Fayetteville to work on the construction of Camp Bragg. Thousands more were scheduled to arrive over the succeeding months.

Despite the Federal government’s promises of food and shelter, the Puerto Rican laborers were at first lodged in crudely constructed barracks that were not properly winterized. Adding insult to injury, they faced discrimination and racial abuses at the hands of white laborers and supervisors. In a sworn deposition, Rafael F. Marchán testified that they were often subjected to threats of physical violence. Several of these threats materialized in the form of brutal beatings, Marchán stated.

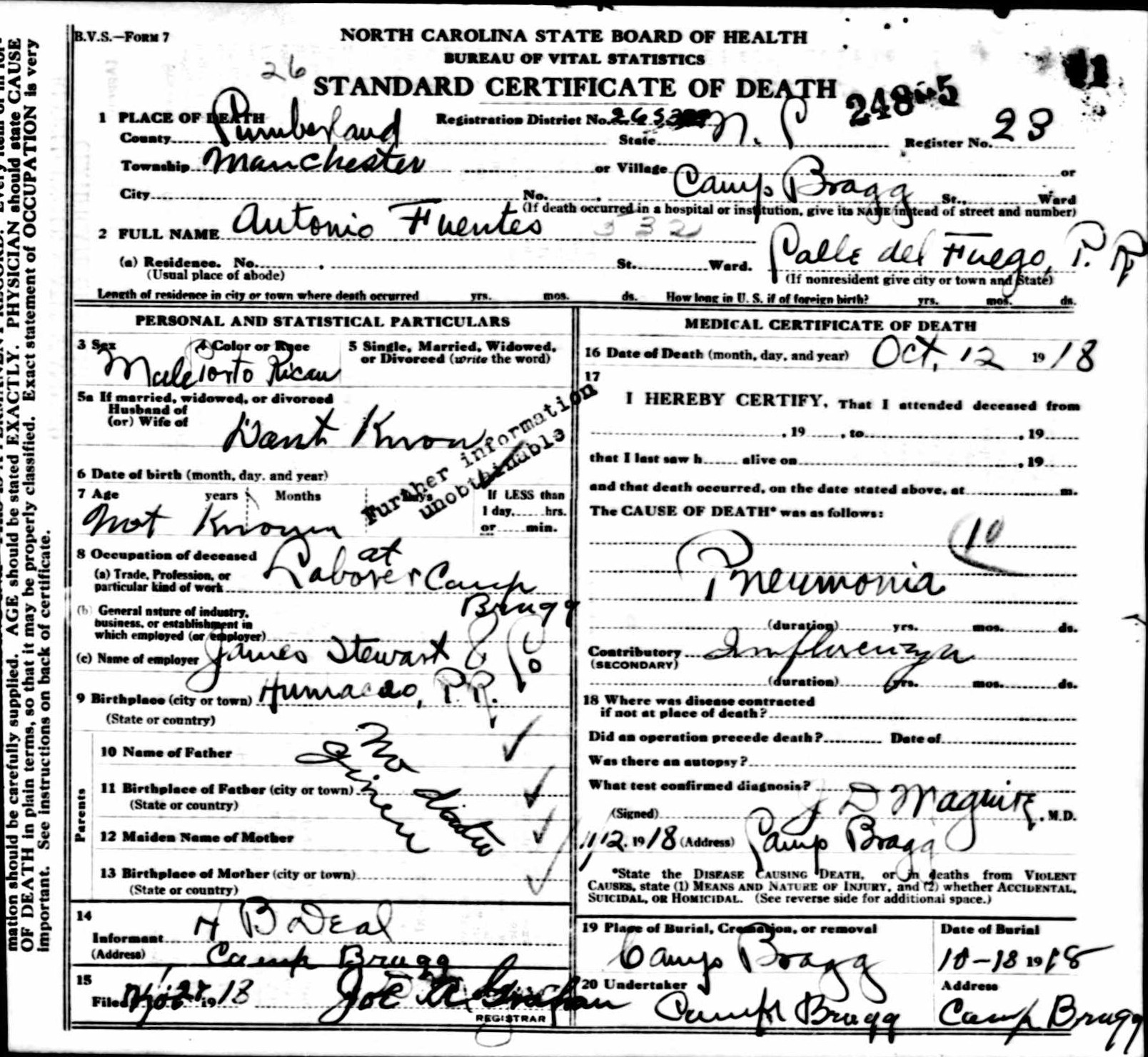

A public health crisis would only further deteriorate conditions for the Puerto Ricans. Within a few days of their arrival, the deadly influenza virus crept into the camp’s confines. Many came down with the flu and were sent to a hospital that was not yet properly equipped to adequately treat the sick. News of the virus’s arrival at the camp spread quickly through Fayetteville. City officials at first tried to downplay the crisis, even going so far as to denounce the news as simple rumor. Despite their efforts at containment, sixty flu patients filed into the hospital within a few days. Click here to view a enlarged version of the inset document.

A public health crisis would only further deteriorate conditions for the Puerto Ricans. Within a few days of their arrival, the deadly influenza virus crept into the camp’s confines. Many came down with the flu and were sent to a hospital that was not yet properly equipped to adequately treat the sick. News of the virus’s arrival at the camp spread quickly through Fayetteville. City officials at first tried to downplay the crisis, even going so far as to denounce the news as simple rumor. Despite their efforts at containment, sixty flu patients filed into the hospital within a few days. Click here to view a enlarged version of the inset document.

In the month of October, at least twenty-eight Puerto Rican laborers perished, most from the effects of the flu. All were buried at Camp Bragg, the first internments in what is now the Main Post Cemetery at Fort Bragg.

A second group of laborers, numbering approximately two thousand, destined for Camp Bragg were stranded in Wilmington when the flu managed to find its way on board their transport ship City of Savannah. News of the Armistice had broke just a couple of days before the ship docked in Wilmington, and the government had every intention of just ordering the ship back to Puerto Rico. The influenza outbreak dashed those plans, however. Health officials transported two hundred of the sickest to a hospital at Fort Caswell for care, while the rest were returned to the island.

Wilmington relief organizations did their best to ease the plight of the Puerto Rican patients, providing clothing, food, and medical care. But the heroic efforts of one person rose above them all. Delaware-born Lena Wright Jason was the daughter of a black Presbyterian minister who moved the family to Puerto Rico sometime at the turn of the century to oversee missionary efforts there. Lena herself grew up learning to read, write, and speak both English and Spanish and went on to attend and graduate from the nursing program at Presbyterian Hospital in San Juan.

Wilmington relief organizations did their best to ease the plight of the Puerto Rican patients, providing clothing, food, and medical care. But the heroic efforts of one person rose above them all. Delaware-born Lena Wright Jason was the daughter of a black Presbyterian minister who moved the family to Puerto Rico sometime at the turn of the century to oversee missionary efforts there. Lena herself grew up learning to read, write, and speak both English and Spanish and went on to attend and graduate from the nursing program at Presbyterian Hospital in San Juan.

With nurses’ training under her belt, the young woman moved to North Carolina to attend Scotia Seminary, an African American women’s college in Concord. Her studies were interrupted, however, by a desperate call for black volunteer nurses in Wilmington during the influenza epidemic. During the crisis, Lena went from home to home, caring for those down with the flu.

In late November, the young nurse was called up for service again, this time at the hospital at Fort Caswell to attend to the needs of the desperately ill islanders. Her command of English and Spanish allowed her to converse with the Puerto Rican patients and to serve as a translator for the medical staff and volunteers. She remained with them as long as she was needed, providing the best comfort and care she could muster.

When the influenza crisis finally lifted in Wilmington, twenty-eight Puerto Rican laborers laid dead. Wilmingtonians looked after each detail of the funerals with pride and gratitude. Funeral processions from Fort Caswell to the National Cemetery typically consisted of white and black members of the Wilmington Red Cross, the fort’s military band, and a military escort detached from the armory.  Funeral services were provided by Rev. C. Dennen at the St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral. At the cemetery, elaborate floral wreaths decorated each hermetically-sealed coffin. Photographers captured the scene so that photos and written accounts of a loved one’s last days could be sent to the families back in Puerto Rico, providing some slight semblance of solace.

Funeral services were provided by Rev. C. Dennen at the St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral. At the cemetery, elaborate floral wreaths decorated each hermetically-sealed coffin. Photographers captured the scene so that photos and written accounts of a loved one’s last days could be sent to the families back in Puerto Rico, providing some slight semblance of solace.

By the end of December, nearly all of the Puerto Rican laborers brought to North Carolina to build Camp Bragg were returned to their homes on the island. A select few remained behind to continue on the camp’s construction teams or to work for the Waccamaw Lumber Company just west of Wilmington.

In the nearly one hundred years since, the contributions of Puerto Rican laborers to the beginnings of the nation’s largest military installation have been largely forgotten both inside and outside of North Carolina. In fact, this story only came to my attention one day as I was walking through the Wilmington National Cemetery and saw their headstones marked with the mysterious phrase “Employee USA.” Intrigued, I went home, looked it up, and was shocked by the story that unfolded. As we embark on the centennial commemoration of the selfless sacrifice of Americans both on the battlefield and homefront, let us also pause to remember and uphold the contributions of our fellow citizens from Puerto Rico.